In 2007, Oakland Police Officer Hector Jimenez fatally shot an unarmed 20-year-old man. 7 months later, he killed another unarmed man, shooting him three times in the back. Jimenez was rightfully fired, but reinstated quickly (Friedersdorf). In Pittsburg, similar fatal incidents occur routinely. According to Alex Zimmerman of the Pittsburgh City Paper:

“In December 2009, Eugene Hlavac was accused of slapping his ex-girlfriend (and his son’s mother) so hard that he dislocated her jaw. And in November 2010, Garrett Brown was accused of running two delivery-truck drivers off the road in a fit of rage… Each of these men, who were all Pittsburgh Police officers at the time of the incidents, shares a common experience: They all were fired, charged criminally, cleared of those charges… and then got their jobs back…” (Zimmerman)

The list goes on and on, and the vast majority of cases end similarly: unnecessarily violent officers ending up back on the force. A 2017 Washington Post report found that “Since 2006, at least 1,881 police officers have been fired from 37 of the nation’s largest departments for behavior that betrayed the public’s trust” (Kelly et al). 451 of these officers got their jobs back, including rapists, murderers, and drug abusers. Why is it so hard to keep dangerous officers from rejoining our police forces? The answer often lies in the protections afforded to police officers throughout the nation at the behest of powerful police unions.

Unionization is the process by which workers in some field (ie. carpenters, engineers, firefighters, etc.) organize together to lobby for increased wages, benefits, and other workers’ causes. According to national data-focused police reform organization Campaign Zero:

A police union contract, also known as a collective bargaining agreement, is the formal working contract between a city and its police department. These contracts control how officers can be investigated or disciplined for misconduct; what appeals processes officers can use to seek reinstatement after being disciplined or fired, whether records of misconduct will be disclosed or destroyed, how much money officers receive in wages, benefits and other funding; and other issues… (Nix the Six)

After the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, a national reckoning on police conduct has thrust these unions into the limelight. Police union arbitration policies ratified by towns and states have received increased scrutiny. Nationally, most police bargaining agreements grant police officers undue rights and overly lenient disciplinary structures that non-police officers are not afforded. While many labor unions are designed to promote workers’ rights and ensure employers do not take advantage of their employees, police unions differ in their especially large influence over local governments, police policies, and police wages, which perpetuates discriminatory police practices and systemic racism; the abusive practices of these police unions must be checked through policy restrictions that limit arbitration and reduce union influence over disciplinary structures.

According to the American Bar Association, “Arbitration is a private process where disputing parties agree that one or several individuals can make a decision about the dispute after receiving evidence and hearing arguments… the neutral arbitrator has the authority to make a decision about the dispute” (“Arbitration”). Police unions are often given the right to request an arbitrator in the case of a grievance and cooperate with the police chief to select a “neutral” mediator whose decision is binding. Different departments have slight variations, such as granting unions and officers complete authority over choosing the arbitrator, and granting individual officers the right to request a specific arbitrator.

Arbitration is not always biased, but the police have managed to skew the process in favor of officers, even unnecessarily violent ones. According to a University of Pennsylvania study of hundreds of police departments, “A little over fifty-four percent of all departments in the dataset give police officers or the police union significant authority in the selection of the arbitrator that will hear a case on appeal” (Rushin 574). Police unions’ main responsibility is to advocate for their officers, and when allowed to select arbitrators who have shown a willingness to reduce or eliminate officer punishments, it makes sense that the organizations would do so. As Rushin explains, “…arbitrators are often repeat players… An arbitrator that frequently sides with either police management or officers during appellate procedures may be unlikely to survive future selection proceedings” (Rushin 545). Arbitrators who frequently compromise on discipline are more likely to be rehired, earning their paycheck at the expense of the public, who face the reinstated officers on the streets.

Such reinstatements are far from unique. For example, in Boston, “Fully 72% of disciplinary actions taken against Boston Police officers are overturned in arbitration…” (Howard). According to former Boston Police Commissioner Bill Evans, “If someone isn’t fit to be an officer, I should have the right to get rid of him… It’s troubling when an arbitrator doesn’t stand behind me when we have grounds for termination” (qtd. in Howard). The vast majority of police departments grant their officers a right to this skewed arbitration. In 2018, Stephen Rushin, a law professor at Loyola University Chicago, examined 656 police union contracts and found that “…the majority of departments allow officers to appeal disciplinary sanctions to an arbitrator selected, in part, by the local police union or the aggrieved officer” (Matthews).

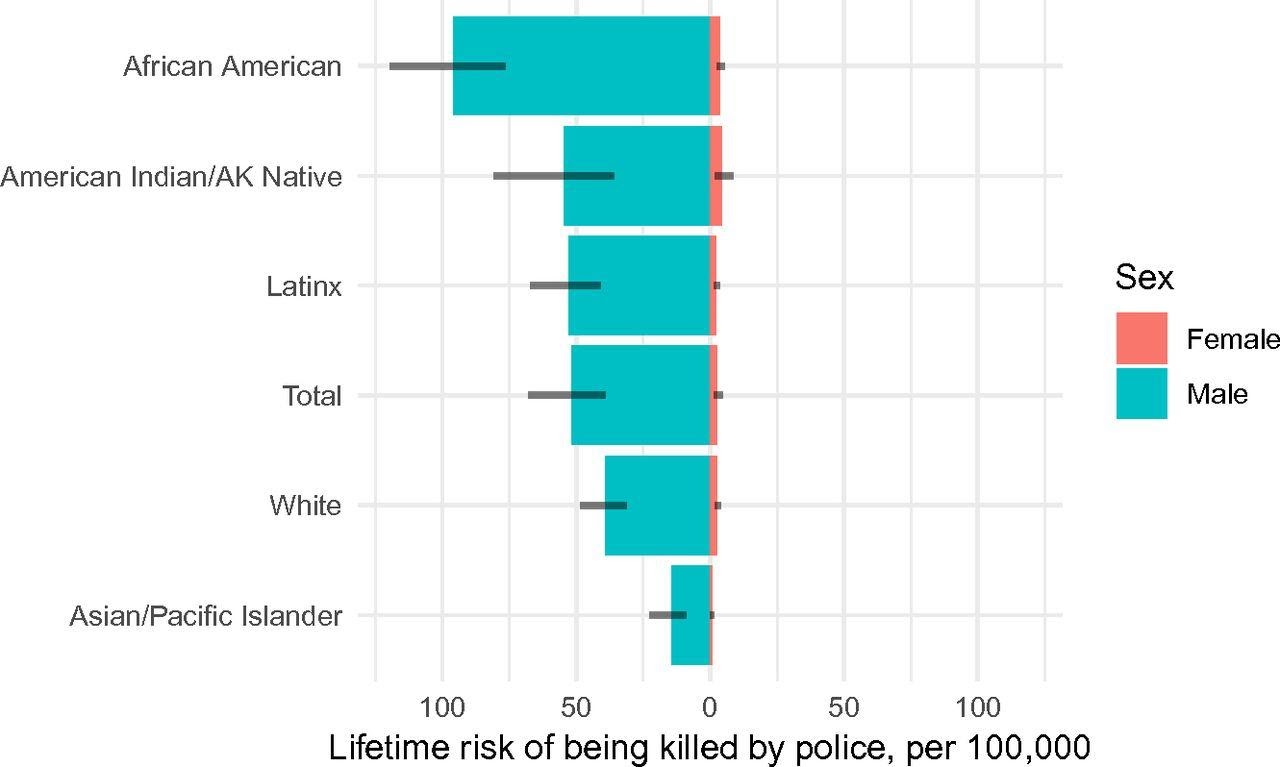

Studies have shown that collective bargaining protections such as arbitration that put problematic officers back on the force after discipline result in police abuse. An analysis of the 100 largest American cities found that “the extent of protections in police contracts was directly and positively correlated with police violence and other abuses against citizens… extending collective-bargaining rights to Florida sheriffs’ deputies led to a forty percent statewide increase in cases of violent misconduct…” (Greenhouse). It is common for officers who commit acts of police brutality, often against citizens of color, to repeat offenses with no accountability. This increase in violent misconduct inevitably increases inequality; data shows black Americans are more likely to be killed at the hands of the police, whether armed or unarmed (Edwards et al).

(Edwards et al)

Further data supports these claims; an analysis of thousands of police shootings found that unarmed black people are killed at a rate 3 times higher than unarmed white people (Belli). These figures lend credence to the claim that the increase in police misconduct due to arbitration would likely correspond with an increase in violence against black Americans.

Police unions throughout the nation inhibit police discipline through their influence. For example, some protections include “…keeping an officer’s disciplinary record secret, erasing an officer’s disciplinary record after a few years, or delaying any questioning of officers for twenty-four or forty-eight hours after an incident such as a police shooting” (Greenhouse). These are protections that only police officers are afforded. Erasing an officer’s disciplinary record after a certain period makes it easier to repeat infractions with no accountability. Delaying questioning for days after an incident allows an officer to consult video footage, fellow officers, and legal counsel about an incident to craft the best account. These provisions implemented by unions are often statewide. According to Campaign Zero: “…Professor Samuel Walker and Kevin Keenan documented in 2005 how police unions helped to enact statewide police bill of rights laws with provisions that constitute ‘impediments to police accountability’” (Nix the six). The impact of these widespread policies has been dangerous. Recent studies show that unions’ “…political and bargaining power has enabled them to win disciplinary systems so lax that they have helped increase police abuses in the United States” (Greenhouse).

Current policy proposals are attempting to reign in union influence over disciplinary structures. Recent Washington D.C. legislation ensures that “All matters pertaining to the discipline of sworn law enforcement personnel shall be retained by management and not be negotiable… future collective bargaining agreements between the Fraternal Order of Police/Metropolitan Police Department Labor Committee and the District of Columbia does not restrict management’s right to discipline sworn officers” (Washington, D.C., Legislature). Similar proposals to curtail union influence over disciplinary structures can tear down the wall that unions have erected between problematic officers and accountability.

Policy restrictions that limit arbitration and eliminate union influence over disciplinary structures are vital to limit these unreasonably powerful unions that exercise dangerous control over local governments, politicians, and police policies, perpetuating discriminatory police practices and systemic racism. It is undeniable that the brutal murder of George Floyd in 2020 shook the American view of policing. Few had realized how union influence has corrupted our police disciplinary systems. Derek Chauvin, the murderer of Floyd, had at least 17 misconduct complaints, several of them for using unnecessary force. Tragically, there are many more officers like Chauvin who are never brought to justice.