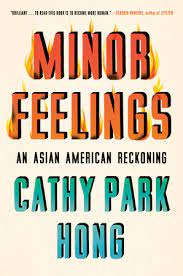

When Cathy Park Hong, author of the fiery Minor Feelings, was in the ninth grade, her teacher insisted that she and her classmates would fall in love with the Catcher in the Rye, just as a gamut of established literary critics had for decades upon decades. She recalls how “I kept waiting to fall in love with Salinger’s cramped, desultory writing until I was annoyed. Holden Caulfield was just some rich prep school kid who cursed like an old man, spent money like water, and took taxis everywhere.” Hong critiques the near-obsessive confluence between American escapism and the nostalgia of childhood, manifesting in several multimedia facets. She finds it quite paradoxical that her youth, while fully American, did not have a tinge of the sensationalized “innocence of youth” that we glorify in films, television shows, and books: her childhood was acutely unstable, rife with the challenges of learning English and the frequent racist rhetoric and attacks that her family experienced.

Hong occupies a very unique space as an Asian-American poet and essayist. Recalling her earlier writing endeavors in a coveted spot at the prestigious Iowa’s Writing Workshop, she saw herself “as a good student of modernism”, effectively deciding that writing about her Asian identity was about the most pedestrian, contrived thing to do. She would not be compartmentalized as an Asian American writer who got acknowledged for her “Asianess”, nor would she be acknowledged for writing about her racial identity. Clearly, she has since graduated from that mindset, penning a series of essays that hold a great deal of candor regarding the Asian American experience and the several stories that conveniently slip through the cracks, even as the enchantment of the model minority fills idealistic discourse. In Minor Feelings, Hong has the upper hand, giving the spotlight to people like her father, someone who defied the conventional Asian immigrant narrative by immigrating to the United States under a lie. Hong remarks that when the 1965 immigration ban was lifted in the United States, only select professionals from Asia were granted visas to the United States, which entailed people who were already doctors, engineers, and mechanics. Naturally, the roots of the successful “American Dream” were first cultivated here, despite only a select number of people being able to enter the country; her father thus had to falsify his occupation as a mechanic in order to come to the United States. Looking back, one can trace the path that has resulted from this “brain drain” to key actions taken by white America to pit minorities amongst each other, using highly educated Asian immigrants as archetypes of the American minority experience, devaluing all other minority experiences.

The spotlight is extended to perhaps the most sobering essay in the collection, titled Portrait of an Artist, wherein Hong covers the life, death, and legacy of writer Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, demonstrating the clumsy nature in which her death was handled by the authorities and the media. Writing about the egregious nature of Cha’s rape and subsequent murder, the essay provides an unflinching commentary on the circumstances in which Asian female bodies are handled in the mainstream, a topic that goes severely undiscussed. This is precisely what Hong aims to discuss in her novel - the unglorified, unsexy stories of minorities that are too repercussive to be palatable.

Hong opens the novel by describing a rare neuromuscular condition that she first developed in her early twenties: known as a hemifacial spasm, she details how this condition would present itself as annoyingly as an uncontrollable toddler, appearing like an imaginary facial tic on the right side of her face, which she would attempt to awkwardly cover-up by hiding her face in public or peering or averting her gaze. Becoming a point of self-consciousness, she asserts that this tic was the starting point of her depression, a depleting parasite that affected her ability to perform, socialize, and carry through her lifestyle. It was at this time that Hong decided to begin seeing a therapist, intentionally picking a Korean therapist because “[she] wouldn’t have to explain [her]self as much”. Much to Hong’s devastation, this therapist would go on to essentially break-up with her following their first session for unexplained reasons, leaving Hong to deal with all of her animosity and dissonant feelings at her lonesome. This experience ultimately parallels the overarching theme of a large portion of these essays in regards to “minor feelings” - when white America demands that minorities deny their “minor feelings” and put on a coat of armor instead;it can often feel like the aftermath of a bad break-up with your therapist. There is no reconciliation of one’s feelings but rather a complete suppression. Left in the debris of unresolved turmoil, Asians are expected to keep their heads down and continue to work hard in order to uphold the facade that America does have a place for minorities, but only the ones that do not complain about the ossified system.

Towards the end of the book, Hong includes this quote from Cha: “Arrest the machine that purports to employ democracy but rather causes the successive refraction of her.” Hong’s persistent message that minorities in America should not have to suppress these so-called “minor feelings” that arise as a result of marginalization is a refusal to put on the so-called “thick skin” as a means to ward off microaggressions. A resounding perspective, Hong begs the audience to consider these minor feelings as not-so-minor - they are indeed feelings with larger implications that are valorized by their mere existence.